By: Darryl Reilly

“Did I ever tell you I wanted to be an astronaut?” “Yeah, you’d be the first junkie in space!” So, converse loquacious heroin addicts with visible track marks, during the opening sequence of playwright Richard Vetere’s gripping, gritty and poetic drama, Black & White City Blues.

It is 1971, in seedy Williamsburg, Brooklyn; three addicts are on a roof shooting up and hilariously philosophizing. While two pass out, one gets it into his head that he can fly and jumps eight stories to his death. A jaded, Latina NYPD detective later arrives, she takes crime scene photographs of the body and investigates; joining her is an intrepid male Village Voice reporter covering the drug scene. Mr. Vetere offers an earthy and compelling urban odyssey, vividly peopled by eloquent substance abusers, sex workers, pimps, and a soulful, ex-addict drug counselor whose son overdosed 14 years earlier. Tragedy abounds.

“I abhor police stations; they bruise my sensibility,” declares a Black trans street walker. “I want to feel nothing, that’s all I want in life,” opines a disaffected addict who takes out a hit job on himself. “She’s a full-time junkie and a part-time hooker,” says a pimp. “The Village Voice is a Commie newspaper,” cracks the cop. Vetere’s articulate, well-crafted dialogue sings and stings, and his plotting in the play’s short, punchy scenes is absorbing, while authentically capturing the grim, underclass milieu of long-ago New York City. Vetere’s gallery of humanely drawn outsiders is intensely brought to life by a supreme ensemble.

(Photo credit: Niko Stycos)

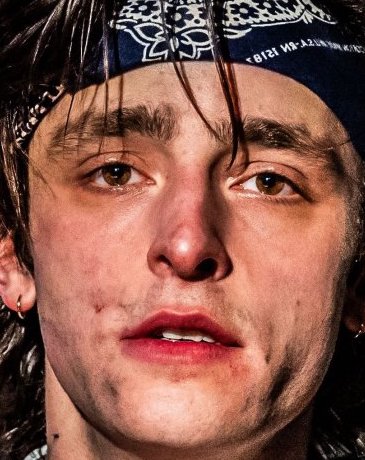

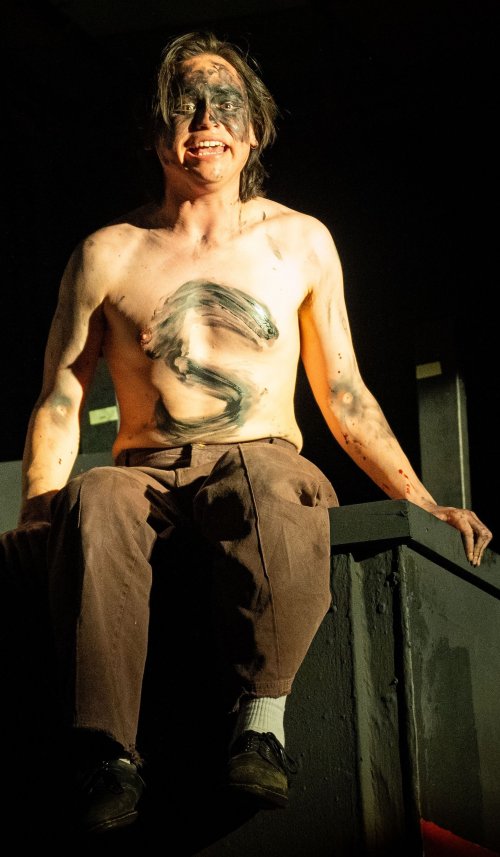

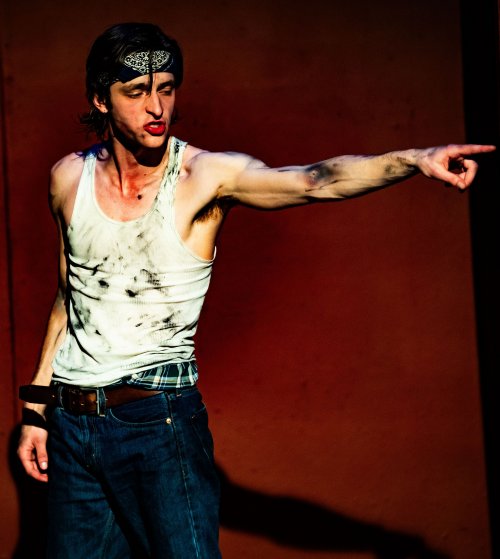

Wearing a white tank top and jeans, the lean, animated and charismatic Joseph Monseur, is electrifying as the play’s central junkie, Little Guy. With his lithe physicality, expressive tenor voice and riveting stage presence, Mr. Monseur delivers a scorching performance recalling the Elia Kazan-era heyday of the Actors Studio. The blonde and luminous Amber Brookes is simultaneously droll and moving as Little Guy’s sex worker, Queens-native junkie girlfriend, Delilah. Ms. Brookes’ spacey speech pattern, focused staring and periodically nodding off with flair, are priceless features of her indelible performance.

The serene Kevin Leonard is majestic as the melancholy, drug counselor mentor. The beaming Jake Minter is delightfully obnoxious as the wired, wastrel junkie son of a Connecticut pharmacy chain tycoon. With his imposing physical appearance and tender vocal tones, Sam Cruz is haunting as Little Guy’s dim, younger brother. Through his superior comic timing, melodious delivery and gruff attitude, the formidable Gary E. Vincent is riotous, yet thoughtful as a salty trans sex worker.

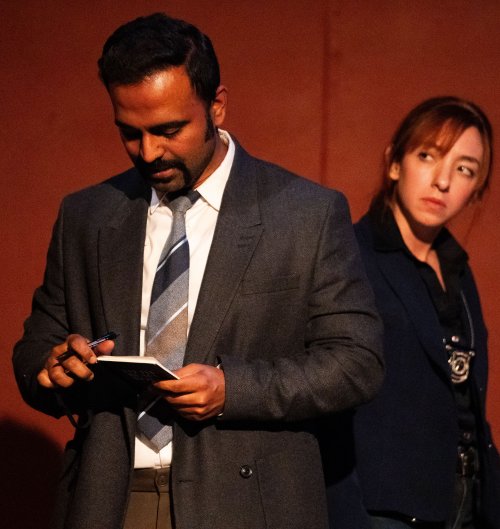

Vivacious Anita Moreno enriches her fierce, seen it all cop characterization with aching humanity. Personable Wasim Azeez as the crusading reporter is charmingly down to earth while getting too close to his story. Magnetic Riyadh Rollins is gleefully funny and seriously menacing as a drug kingpin named Piranha.

An eerie, absurdist family dinner dream sequence at a long table is staged with glorious Peter Greenaway-style picturesqueness, and is a highlight of Ms. Brookes’ prodigious, snappy direction. The cast of nine are always strategically positioned, there are precise entrances and exits through the auditorium, and the space is artfully utilized, particularly in the above the audience rooftop sequence.

Breathtaking violence occurs, injecting heroin is realistically depicted, and despair pervades. The simple, yet evocative scenic design chiefly consists of weathered maroon wall panels, a streetlamp, basic furnishings and a neat neon bar sign. Offices, various exteriors and the bar, are all clearly rendered and swiftly transitioned to, due to the sharp blackouts contained in Jake Smith’s appropriately moody, and atmospheric lighting design. Bracing effects and wistful incidental music are realized by the adept sound design.

Sadness, lightheartedness and realism, all converge in the searing Black & White City Blues.

Black & White City Blues (through February 9, 2025)

American Theatre of Actors, 314 West 54th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit www.americantheatreofactors.org

Running time: one hour and 40 minutes with no intermission