Hello. I’m a friend of Joe Aliaga’s and I’m sorry to have to tell you that he passed away on Christmas Day. He gave his friends a list of people he wanted to know. There’s going to be a memorial service. You’re more than welcome to attend. It would be nice if you could come. There’s going to be lots of people. Again, I’m sorry to be the bearer of sad news. He was ready, and wanted to go, and he is now at peace. Thank you. Bye bye.

I was a client of the psychologist Dr. Joseph Aliaga for 11 years and was touched to be on the list of those to be notified by phone of his death at the age of 82.

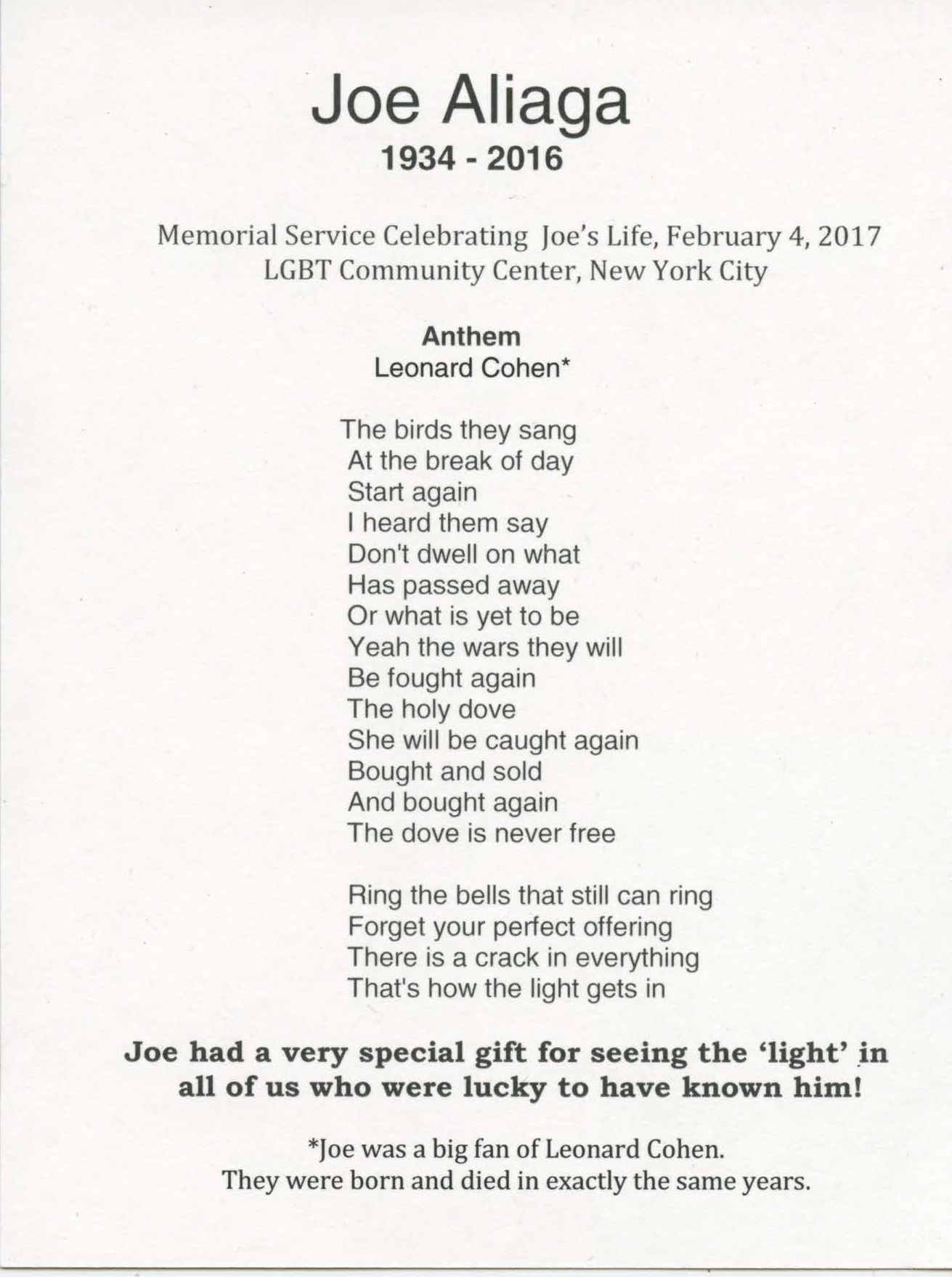

The memorial tribute to him was held on Saturday February 4, 2017, at The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center at 208 West 13th Street, in Manhattan. Joe was gay, and had been a prominent figure in the New York City gay community.

The event took place in the large Lerner Auditorium on the third floor, and more then 50 people attended. Long tables in the back had platters of small sandwiches, cheeses, fruits, soft drinks and coffee. I arrived 15 minutes before the 1:00 PM starting time.

As I was walking around a man introduced himself to me. When I responded, he knew about me. “Joe spoke of you often.” It was the first of several such amiable, uplifting and informative conversations.

I saw an actor who was a client of Joe’s. Joe had once urged me to see a play that he was performing in. I did, and so went over to tell him all this. This led to a pleasant conversation. There was such collective grief and warmth, that strangers easily interacted.

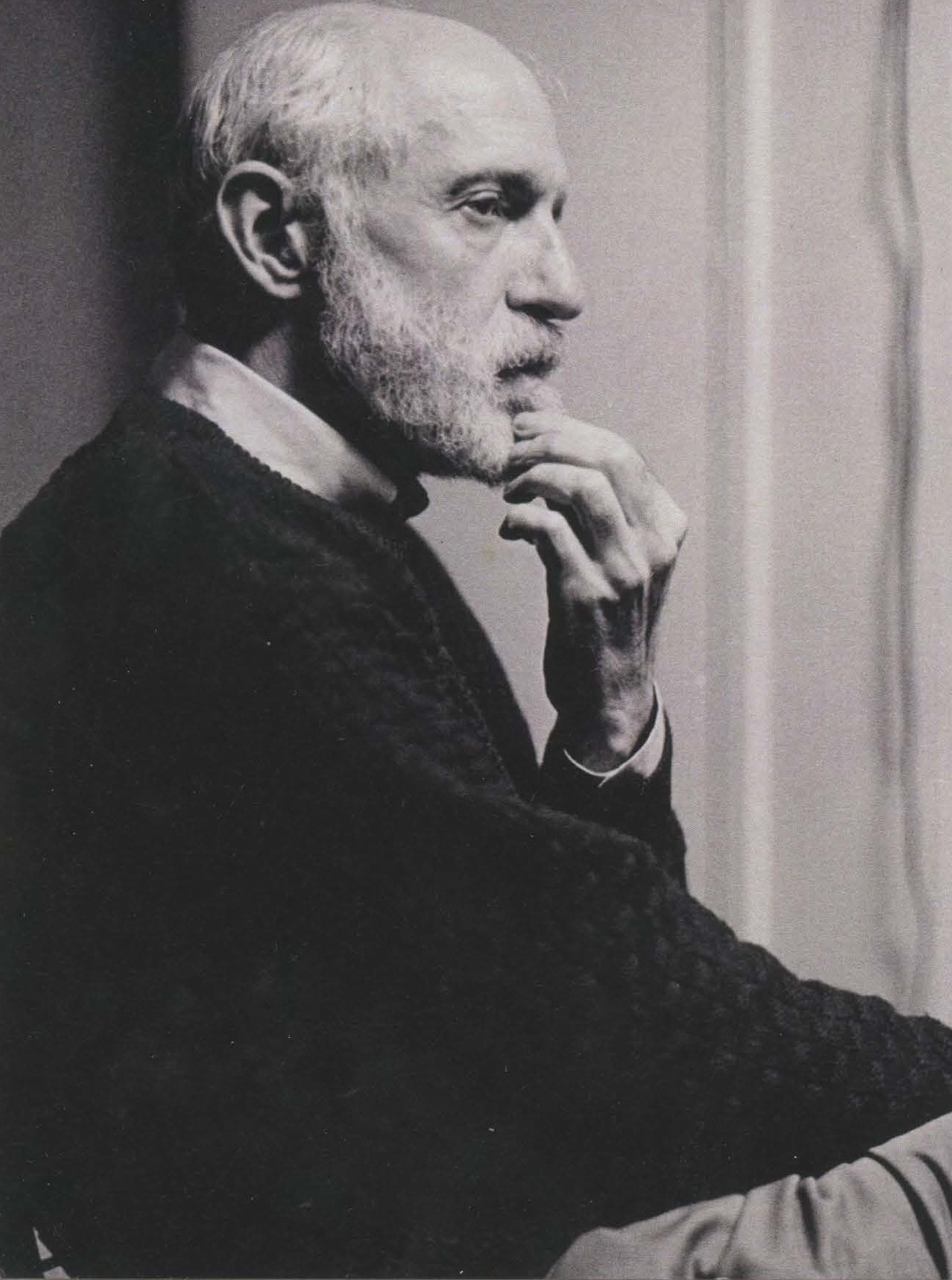

On a large screen was projected a selection of photographs of Joe with biographical information. He was born in Brooklyn, his schizophrenic mother was Puerto Rican and his absent father was from Spain, he had a paternal half-sister, he had been a tour guide and a bus driver, a transit union representative and an unpublished novelist of several books. That he got a degree from NYU and became a therapist at the age of 40. There were pictures of him from all ages of his life, and of the places around the world that he traveled to.

His ardent animal rights activism was rooted in his life-long love of his childhood pet, a beagle named Popcorn.

Glenn Gould’s recording of Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier was played during this presentation. Later, we were told that this was one of Joe’s favorite pieces. At the end of the event, one of Joe’s favorite artists, Leonard Cohen, was heard singing his song “Anthem.”

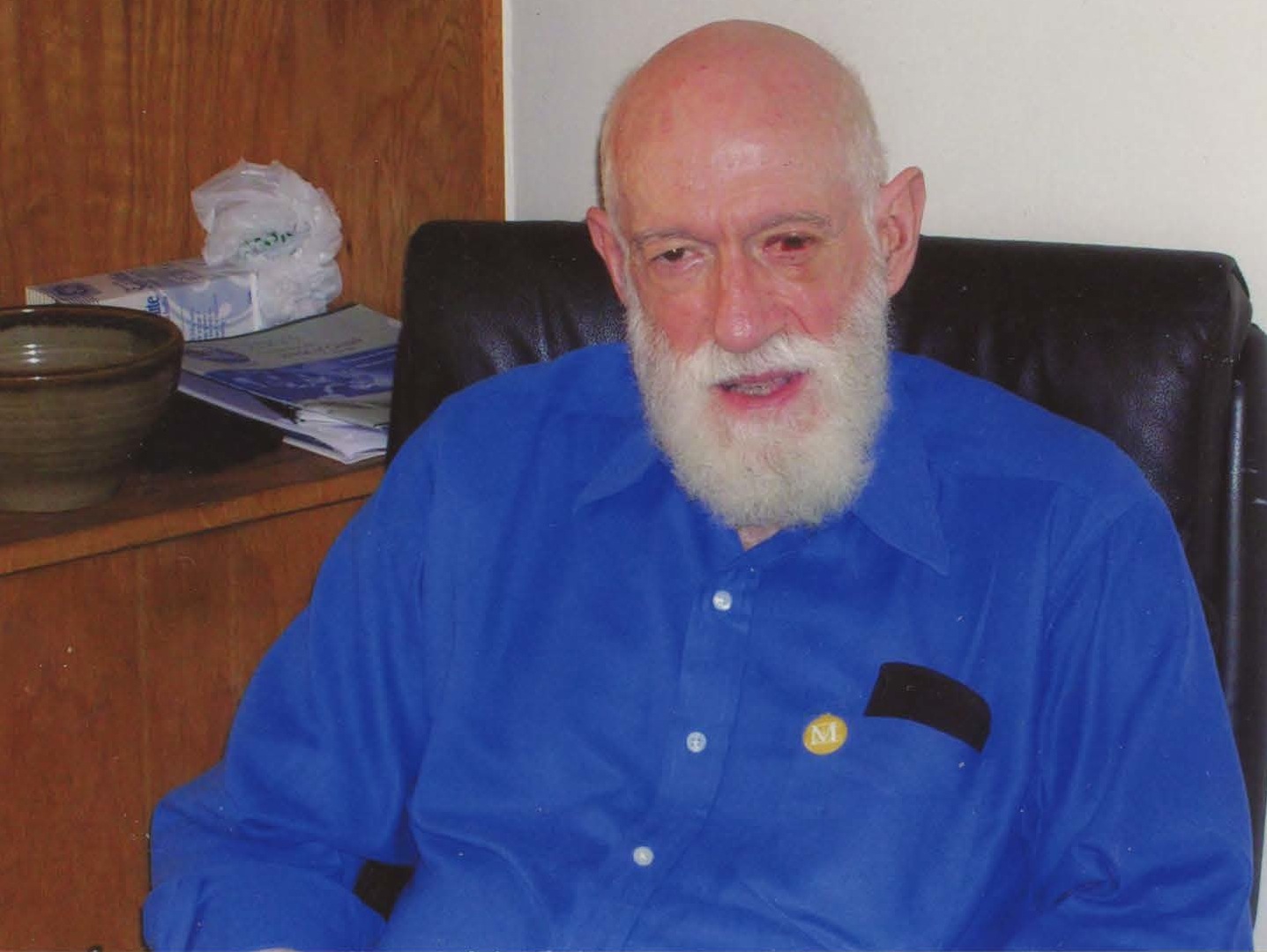

There were tall, standing boards with photographs of Joe, and also a table with photographs. These were all used in the slide show, and there was a sign encouraging people to take any they wanted as a souvenir of him. I took the one of him in a blue shirt that accompanies this story, as it is how I remember him.

Two small crates from Joe’s extensive and eclectic CD collection were on display and people could take whatever they wanted. I took an Edith Piaf set, Lena Horne at The Supper Club in 1994, a Frank Sinatra 80th birthday collection and the two disc The Essential Bob Dylan released in 2000. Joe and I had often spoken of music over the years, and it was fascinating to actually see what great and far ranging taste that he had.

Joe was long affiliated with Identity House which was founded in 1971. It is “a peer-counseling center for the community offering a walk-in counseling and referral center as well as weekly groups where people can talk about issues related to sexual identity.” He moderated many groups there.

Officials from Identity House organized and presided over this more than two-hour glorious remembrance. They spoke at a lectern with a microphone, and then anyone else could either go up to the front, or have the microphone brought to them.

About a dozen attendees shared their memories of and experiences with Joe. A common theme was his concern for his clients and his generosity. How his fees were often so low, so that no one was turned away due to lack of funds, as he nobly believed that anyone who needed therapy should have the opportunity for it. This was a factor of his financial insolvency in his later years.

Another link between many of those who spoke was the long length of their time with Joe. One person had been seeing him for 22 years, and most had been doing so for over 10 years.

A young man spoke of how he came to Joe at the age of 19, troubled by his family’s negative response to his being gay. Joe helped him get into college, and that led to a successful career.

The landladies of his office on West 13th Street humorously recalled their relationship, notable for his lack of aptitude with technology. That was a recurrent reminiscence.

A man who became a client after having been traumatized by his involvement with 9/11, described how after changing careers and becoming computer specialist, he went from being a patient to being friend of Joe’s. Joe often beseeched him for computer help for “that fucking thing!” It was speculated that Joe might have had an undiagnosed learning disability.

Joe’s passion for the arts was chronicled and he had many clients in the field. A devoted moviegoer, his colorful film reviews were legendary. One person detailed Joe’s lengthy, serial phone messages that were movie critiques worthy of The New York Times.

I remembered his story of visiting his local hardware store and seeing fabulous paintings hung near the cash register. The owner of the store did these. Joe tried to interest an art agent patient of his in them. “I have so many clients that I can’t get any attention for already. I can’t take anyone else on,” was the pragmatic response.

An Indian man movingly told of his 30-year involvement with Joe. With Joe’s encouragement he pursued his passion for writing and this culminated with the recent publication of his book of short stories. Alas, this was too late for Joe to see this.

On the lighter side, a heavy-set male client of Joe’s sang a hilariously compelling rendition of the classic “Twisted” song, “My Analyst Told Me.”

It was recalled that Joe believed that happiest times of his life were in the free-spirited era of the 1960’s Greenwich Village coffee houses. His Leftist and very Liberal politics were discussed. He was warning all year that Donald Trump had a very good chance of winning the presidential election. Joe based this on his long ago days as a cross-country bus driver, and his knowledge of life outside of New York City. “I know how those people think!”

An older friend of Joe’s refreshingly brought up his earthiness. “Joe traveled around the world, but he didn’t spend all his time in museums!” He lightheartedly went on about Joe’s sexual exploits that continued on into his later years, and how though he urged others to settle down, but had no interest in doing so himself.

A very emotional series of recollections were from a man in his 20’s, who was a volunteer with SAGE (Senior Action In A Gay Environment). He detailed how during the last year of Joe’s life he regularly visited. They would watch movies and he would read aloud to Joe, but they never finished any of these works as Joe would tire. How forgetful Joe had become, and how they would converse about the same things each week. It was a beautiful case of the very young helping the very old.

Joe’s physical and mental decline began in 2012, when he slipped on an icy street and broke his shoulder. It was after that, that we switched from office visits to phone sessions.

In January 2016 after getting off a bus he fell in the snow and hobbled to his office for a therapy session. The patient asked if he was all right, as he appeared to be in pain. Joe described the incident and the patient looked at his monstrously swollen knee and demanded that they go immediately to a hospital emergency room. They did, and the fractured knee was diagnosed.

After surgery, Joe had to go into a nursing home for rehabilitation. His stay turned out to be permanent, necessitating giving up his East Village apartment. A close circle of friends and colleagues took care of his needs until he died.

I visited him only once at the Upper West Side nursing home that he had been transferred to. That was because he made it difficult, and I sensed he had mixed feelings about me seeing him while he was in less then ideal condition.

We spoke on the phone. He had an old flip, cell phone. I expressed the desire to see him. We set up a date a few days ahead. I called that morning, and he said it wouldn’t be a good time and set up another visit. I called that morning and he said okay. An hour later, while I was on the subway he said not to come. A week later I went over without advance notice.

I had not seen him person for three years. He was wearing a hospital gown, and was in a wheelchair, with his knee heavily bandaged, and had lost a good deal of weight. He was poring over an old notebook, writing in it with a pen. He was happy to see me.

We caught up, and he was unhappy about the facility, and was making plans to go somewhere else, which never happened. He was rueful, “Oh, Darryl, it’s not good…”

I was there about a half hour, and he said goodbye and so I left. We spoke a few more times on the phone. One time he asked if I would visit. I said yes, and it was left that he would tell me when. That never happened. Once, I had voice message where he just bellowed my name. I returned the call but never heard back. I called again and didn’t get a response.

I felt guilty about not having been more in contact with him. During the tribute though, someone went on about how Joe didn’t believe in guilt, especially when we are faced with difficult situations that we really have no control over and have to make a decision. I did my best under the circumstances, and I felt he knew that, and that he wanted things to be as they had turned out.

“I was one of Joe’s low-fee patients,” I said in beginning my reflections. It was near the end of the tribute. I had been wavering about getting up to speak, and it was now or never. “Every few years, he would reluctantly ask if it was possible for me to pay $5 more.” I then told my story about Joe and me.

After feeling overwhelmed by several situations I went to Identity House’s drop-in counseling at The Center and spoke to a very sympathetic counselor. He set up an appointment at Identity House. I spoke with someone there and was then given the names of two therapists to make appointments with.

The routine was to have a prospective client meet two possible therapists and give them a choice of whom to go to.

The first was a nice man in his early 30s, who classically mostly listened in silence with occasional “Ahs.”

The second was a bearded, loquacious and bald old man with twinkling eyes. He was a cross between Sam Jaffe and Ralph Bellamy in Rosemary’s Baby. That was Joe. Though not Jewish, his patter was sprinkled with Yiddishisms, and he came across as an old-time, street smart New Yorker.

“I’m 70. I wanted to be a writer and wrote six novels that I couldn’t get published. I eventually became a therapist. Many of my clients are artists and performers. I know what the frustration is like of being an artist…”

I told him of my feelings and situation. By the end of this introductory exchange, I thought that he was clearly the one to go to.

Into the third year came what I believed to be the great breakthrough that made the therapy invaluable. While we were conversing he proclaimed:

“You seem much more hardened then when we started.”

“Thank you doctor! Then it’s not my imagination! I do feel less hurt and vulnerable. It takes less time to get over setbacks and disappointments then it used to.”

“What do you attribute that to?”

“It could be the therapy and it could be just getting older. It’s probably a combination of both.

“I think you’re right.”

The years went by, visiting Joe at his office weekly. Past traumas were explored and present ones analyzed. He was particularly insightful regarding my relationship with my difficult mother. He briefly alluded to his own mother, and learning years later that his mother was schizophrenic, and had been institutionalized, must have given him a unique perspective on the subject.

Many times we got caught up in discussing movies, plays and musical performers. It was not unusual to for there to be a 20-minute detour onto the greatness of Humphrey Bogart, Frank Sinatra or some other ionic figure.

He was constantly affirmative about my acting ambitions. “You have a great presence and are very funny. I could see succeeding on the stage. Keep at it!” “Any auditions this week?”

From inquiring of another client of his who was a moderately successful actor, he brought in a list of helpful hints for joining the performing unions and about contacting agents that he shared with me.

That I was single was another facet of his concern. I was encouraged to join online dating sites. “Go to bars but watch the drinking.” He was overjoyed when I eventually entered into a significant and lasting relationship for the first time.

Following the first six years, after the past had been mined and the present was better, our sessions took on a more conversational tone.

There was a month long hiatus into the eight years when he was recuperating from his broken shoulder. Then began the phone call era as he had to cut back on seeing people in his office. Talking once a week on the phone became a ritual of debatable benefit.

Last year, the day before our phone session he called me to say he would have to call me later then we planned. This was due to his being in the hospital for his broken knee.

“We won’t be able to talk today,” was his message the next day. I could hear him yelling with pain. It was left that he would let me know when we would continue.

Two weeks later there came an awkward and brief conversation as he announced that we wouldn’t be able to continue at all because of his condition. I was relieved and sad at the same time.

“No matter how long you go, the last four years weren’t necessary,” was Nora Ephron’s remark about therapy. As usual with her quips, this pithy pronouncement is humorously true.

Indeed, years into therapy I questioned to myself about whether I should stop. Several times during the phone call era, I almost did. Joe was declining. He couldn’t remember things, and I would have to give a recap/summary of subjects we had discussed many times before. There was even a time when he called me by someone else’s name and once asked who I was.

A portion of each session would be devoted to the checks I sent. Did I send it? He got a check. What weeks did it cover? He got confused about the date of a check. Still, I continued our sessions.

Friends were aghast that I still went on with him. I felt he had helped me considerably and that I was now helping him. He obviously didn’t want to give up. Like most people in their later years, he wanted to be useful and to have something to do. Besides, his fee was very low and I still believed in the benefits of talking to a professional, even with diminished capacities.

Our later conversations could be exasperating, but there were also chats that were fulfilling. That it came to an end due to his wishes seemed natural and fitting. He offered to refer me to someone else, but I declined.

The paradox is that though I agree with Nora Ephron I now miss those phone calls. When I concluded my remarks I felt the eerie sensation of wanting to tell Joe how well my speech had been received by several people there afterward.