There were so many brave young actors and actresses whom one felt were brilliantly talented, but their genius crashed against the morbid rocks of indifference and stupidity represented by casting directors, directors and even writers, who seemed to view theatre as an aspect of themselves and a mirror for their own limited world, whereas the actors’ world was a different mentality.From Free Association: An Autobiography by Steven Berkoff (1996)

For nearly 50 years, Steven Berkoff has been an iconoclastic titan of the theatre in his native England, and around the world. A visionary purist that has rarely been affiliated with a major theatre company, he still heroically has achieved a tremendous career as an actor, writer and director.

On August 3, 2017, he will be 80 years old. I, and his many other admirers wish him a very Happy Birthday.

I prided myself on being able to speak and move, and on the fact that I had taken the actor’s body as seriously as his voice, mind and totality of his equipment.

Possessed of a resonant, booming and expressive voice that often soars with bravado, and a lithe and commanding physicality, he has been a vibrant exponent of these beliefs. Then there are his fierce eyes, animated face and innate charisma that all add up to a thunderous presence. These traits have made his performances in his own unique theatrical creations, landmarks in the history of the performing arts.

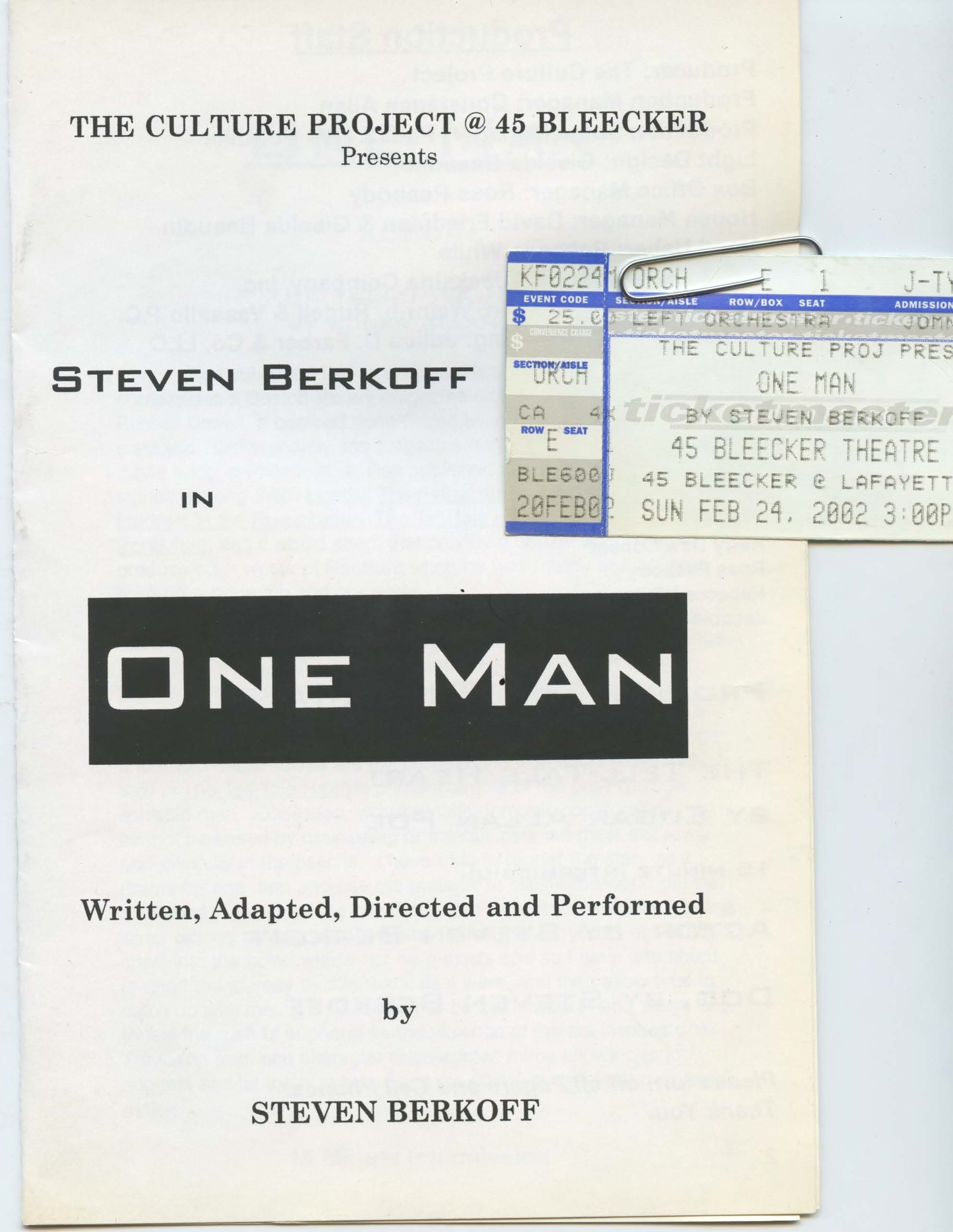

In early 2002, Mr. Berkoff appeared in New York City in his solo show, One Man at The Culture Project (now the Lynn Redgrave Theatre) on Bleecker Street. I was so overwhelmed by his performance in this, that I was compelled to see it again a few weeks later. It is the work of theatre that has had the most influence on me.

To call it a monologue does not do it justice. This was a virtuoso display of mime and physical and vocal pyrotechnics, all resulting in a spectacle of grand stage acting. It was composed of three parts that he wrote, two of which were original pieces.

The Tell-Tale Heart was his eerie adaptation of the Edgar Allen Poe story. Dressed in black, with tails and a white ruffled shirt he portrayed the narrator, who has been driven to murder by obsessing over an old man’s malformed eye.

The breathtaking highlight was Berkoff meticulously miming sprinting down a long, narrow spiral staircase to let the police in. He acted out the parts of the inspectors, the old man and various sound effects with his expressive face, fluctuating voice and epic gestures. These effects were all accomplished with swiftness on the bare stage.

Actor ingeniously and poignantly dramatized the existence of a typical actor. Mesmerizingly running in place while center stage, he recounted auditions for roles not gotten, contentious meetings with casting agents, and colleagues getting breaks. Years pass, as he is running but not really getting anywhere. We learn that his amiable parents have died, that his girlfriend has left him, and he is ultimately alone. It was a heartbreaking, hilarious and painfully accurate depiction of the actor’s life.

In Dog, he portrayed a crass, racist, xenophobic loud-mouthed football devotee and his vicious dog. With his neck elongated, his teeth and tongue extended, he assumed the physiognomy of a barking canine. The dialogue alternated between the man’s bellicose observations and the equally unpleasant thoughts of the dog. It was a riotous and provocative tour de force.

The lobby walls of the theater were adorned with printed blowups of his poem, Requiem for Ground Zero that expressed support for New York City in the aftermath of 9/11. Following the second time I attended, I waited in the lobby with my copy of Free Association, along with other fans.

Previously I bought one of the pre-autographed black and white pictures of him that was on sale. I selected the one of him from The Tell-Tale Heart, where he is stooped, with his feet bent as if to scurry down the imaginary spiral staircase. I later had it professionally framed and am looking at it now on my living room wall.

Eventually, The Great Man wearing a voluminous, battered leather coat, and a cap emerged, and slowly made his way through the lobby. People congratulated him. Smiling slightly, not making much eye contact, and with the clipped and melodious tones of his idol Laurence Olivier, he proclaimed variations of, “Thank you. Thank you very much. You’re too kind.” It was if he ware impishly acting out the part of a great actor besieged by his fans.

“Would you please sign this?” I extended my copy of his book and he scrawled his name in it. After thanking him, I went out into the cold exhilarated by his performance, the encounter and obtaining another memento.

Besides these souvenirs, more profoundly what I took away from these experiences was the burning desire to be able to do what he did.

Fixated by wanting to be an actor since childhood, I had taken a circuitous path. Not having been a theater or acting major in college, I started from scratch in my early 20’s. I took scene study classes and then began auditioning, and got roles in small productions here and there.

“You’re a little stiff, but that’s okay,” said a director who cast me in an Ionesco play just before it went into rehearsal. I had been getting by, and performed well, but felt physically and vocally limited.

After seeing One Man, I enrolled in several movement and voice classes and made progress. A few years later at an audition held at The Culture Project, I was overcome inside with emotion to be standing on the same stage where I saw Steven Berkoff perform.

Never having made it into Actor’s Equity, my audition opportunities were limited, but I managed to perform in numerous of showcases in a variety of parts, all enriched by the epiphany of seeing One Man.

The most lasting impact of that experience has been on my profession as a New York City sightseeing guide. This involves routinely taking large groups of tourists on the subway, walking around and delivering commentary without a microphone.

I am perpetually conscious of projecting and varying my voice, circling and pacing around so as to make sure everyone hears the material that I know backwards and forwards, and which is seamlessly delivered. All while gesturing gracefully and emphatically, while my eyes and features convey feeling.

Mentally I become the narrator of The Tale-Tale Heart, the actor and the skinhead and his dog. I am hurtling down that spiral staircase in my mind.

I first became aware of, and was fascinated by Mr. Berkoff in the 1980’s, from his magnetically villainous screen performances. Octopussy, Beverly Hills Cop, Rambo: First Blood Part II in quick succession established his name recognition. Then there were his notable appearances in Revolution, Absolute Beginners, and Under the Cherry Moon, and as Adolph Hitler in the television mini-series, War and Remembrance.

In November 1988, he directed Christopher Walken in Coriolanus at The Public Theater. A few months later, in March 1989, he directed his adaptation of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, starring Mikhail Baryshnikov on Broadway.

In that era, I read everything I could find about him, including his plays. Harry’s Christmas particularly struck me. It’s a 17-page, bleak monologue delivered by a lonely, disaffected man in his room. He measures his life by the amount of Christmas cards he receives and relives his past through his collection of them that he displays. At the end he dies by suicide.

You score six miserable Christmas cards…Christmas to make you feel like you don’t exist…if I don’t get more than six I’ll definitely put up two from last year…maybe three… Why save them? …They remind me…It’s a piece of memory…Those two…not seen them for years…but every year they send a card and I send one back…so they know I’m still alive…

In the 1990’s, I was attending Anne Jackson’s scene study class at HB Studio. Due to my Bronx cadences and idiosyncratic speech pattern, I was most often selected to be in comedies. Like virtually all actors I wanted to prove my versatility, and decided I would perform an extract of Harry’s Christmas. I saw it as a great dramatic vehicle for myself.

I practiced and practiced and had the words down perfectly. I did not feel capable of using an English accent but it’s a universal story. I Americanized a few things such as television for telly.

After setting up some basic furniture and holding the Christmas cards I had brought with me, I began. I could feel the rapt attention of the students in the classroom as I expressed despair and emotionally erupted. Soon there was LAUGHTER!

Though disconcerted, I didn’t miss a beat, and went on with my histrionics to the continued sounds of merriment. My goal had been foiled. The piece does have funny sequences but I was immaturely consumed with being serious. Anne Jackson was quite complimentary. So far, that is the only Berkoff role I have attempted.

I finally got to see him onstage for the first time when appeared in New York City in January 2001. He brought his acclaimed solo show, Shakespeare’s Villains to Joe’s Pub. It was a galvanizing event where he performed portions of the roles of Richard III, Iago, the Macbeths and others. Interspersed was his insightful and irreverent commentary.

The summer of 2002, several months after seeing One Man I was in London, and was browsing in a used book shop near St. Martin’s Lane, before a matinée. On a shelf in the theatre section I saw the black spine of a jacketless hardcover volume that in gold lettering said, The Theatre of Steven Berkoff. Published in 1992, it’s a lavish assortment of stunning black and white photographs documenting all of his productions up until that time, accompanied by his informative text. I went to the counter to pay the £7.50 for it.

“Oh, he comes in here often,” said the bespectacled, middle-aged male clerk. “He’s quite a character.”

For more information visit: www.stevenberkoff.com

www.iainfisher.com/berkoff/index.html