By: Darryl Reilly

Note: This was published at Theaterscene.net in April 2020; I had been a critic there for six years. In July 2022 I had a falling out with that site’s owner Jack Quinn and its editor-in-chief Victor Gluck. Out of spiteful retribution for leaving and creating Theaterscene.org, this is one of 70 + articles of mine they deleted. Quinn and Gluck did not get in touch during the initial days of the pandemic; there was no call to arms. On my own, I wrote a series of musings and memories that were special to me. I have reconstructed this from the Word document, without the pictures included in the original posting.

“How should we end this movie? If you don’t know how to, turn out the lights and say, ‘The End’” states María Irene Fornés near the conclusion of this fascinating documentary about her, The Rest I Make Up. Much of director Michelle Memran’s footage is from the early 2000’s, depicting the vibrant, cheery and Bohemian Ms. Fornés’ struggle with Alzheimer’s disease while living in Lower Manhattan. “How many years has it been since I began forgetting things?” “Five.” “Five years? Wow.” Ms. Memran’s friendship with Fornés started in the 1990’s and their closeness informs her affectionate and informative portrait.

https://www.therestimakeup.com/trailer

The Cuban born Fornés emigrated to New York City in the 1950’s, started writing plays in the 1960’s and by the 1970’s became a major figure in the theater. Her work was joyously avant-garde, without the embrace by the establishment, she eventually faded into relative obscurity. Among her many prestigious honors are nine Obie Awards. She died in 2018 at the age of 88.

“She was the love of my life” the gay Fornés recalls of her passionate failed relationship with Susan Sontag in the 1960’s. “I run into him every few years, we’re friendly and then that’s it” Fornés forlornly observes after a chance street encounter with colleague John Guare.

As Fornés’ Alzheimer’s progresses, her sister plans to move her to Miami. “I need to stay in New York because I’m a playwright.” “You haven’t written anything 10 years.” “Really? I haven’t written anything in 10 years?” The Rest I Make Up is streaming for free on Vimeo and Kanopy.

Ed Asner is shattering as a feisty Holocaust survivor battling contemporary imperious Jewish bureaucrats in playwright Jeff Cohen’s provocative The Soap Myth. Magnetic performing arts veteran Tovah Feldshuh fiercely plays a Jewish scholar and British Holocaust denier. Ned Eisenberg offers sharply distinctive characterizations in five roles. As a young Jewish journalist balancing truth and morality, Liba Vaynberg is captivating.

After the Nuremberg Trials, it was widely accepted that among the Nazi’s’ atrocities was transforming the corpses of Jewish concentration camp inmates into soap. However, over time many Holocaust scholars had come to discount this claim due to a lack of physical and written documentation. Mr. Cohen skillfully renders this charged conflict with his appealing characters and command of dramatic writing.

First developed in 2009, director Pamela Berlin’s focused and smooth concert-style reading format of The Soap Myth has been touring the U.S.A. since 2016. This incarnation was taped on April 22, 2019 at the Center for Jewish History/YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City and is streaming for free on WNET’s ALL ARTS platform.

An Amazon gift card inspired me to obtain Kindle editions of two books I’ve been keen to read.

“The kindest man I have ever known” said Al Pacino of famed New York City film director Sidney Lumet who died in 2011, at the age of 86. Their intense collaborations on Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon are detailed in Maura Spiegel’s rich biography, Sidney Lumet: A Life.

Lumet’s half-hearted, though real suicide attempt at the age of 39, as his marriage to Gloria Vanderbilt was ending, is one of several revelations contained in the book. Other painful and formative situations include Lumet’s depressed pregnant mother’s harrowing death when he was 15 years old and his long and strained relationship with his flighty Yiddish theater actor father Baruch.

Ms. Spiegel’s style and structure are as down to earth and technically accomplished as her subject’s movies with chronologically shifting jump cuts. Extensive interviews with Lumet’s four wives, friends, relatives and colleagues, material from his attempted autobiography written in his 70’s, his father’s oral history interview and unpublished memoir, are all incorporated into Spiegel’s full-fledged portrait of the man and the artist.

Being a Columbia University film and literature professor informs Spiegel’s insightful examinations of specific sequences from 12 Angry Men, Long Day’s Journey into Night, The Pawn Broker, the wife’s aria in Network, and spatial qualities in Prince of the City. Many of Lumet’s 40+ other films get barely a mention, which is arguably understandable due to length considerations. In addition to cinematic analysis, there is psychological analysis. Lumet was more than just his jeans-wearing gutsy New Yorker persona.

The familiar saga of the Lower East Side-reared Lumet’s child acting career, W.W. II service, supremacy in the live television era and then his emergence as feature film director are chronicled with precise depth. His childhood was more grim and complicated then Lumet let on in interviews. His helplessness witnessing a sexual atrocity by U.S. soldiers on a young girl during the war in India left a profound mark. Not being invited back into the Actors Studio after its first year was traumatic and led him to becoming a director. His heroism during the Blacklist, these, and many other events are dissected and connected to the films, proving autobiographical links to some, particularly Daniel.

Pauline Kael’s treacherous inside coverage of the making of The Group is cited, and her perpetual disdain of Lumet is countered by the enduring appeal of much of his work which Spiegel masterfully expounds upon.

In 400 characteristically witty pages, Woody Allen achieves two goals in his sparkling memoir, Apropos of Nothing which reads with the sound of his voice in one’s head. As an autobiography of a theatrical celebrity mired in controversy, it recalls the assured defensiveness of Elia Kazan’s monumental, A Life.

Mr. Allen describes his Brooklyn Jewish childhood with grand nostalgia and details his dense but loving mother and ne’er-do-well father with affection. Allen’s phenomenal show business career that began as a teenager selling jokes to New York City newspaper columnists, writing for television comedy shows in the 1950’s, emerging as a major standup comedian in the 1960’s, writing two hit Broadway plays a long the way and his rise in the 1970’s as an acclaimed film director, is breezily charted through engaging anecdotes and humorous observations.

Exploring his enduring relationship with Diane Keaton that began as romantic and developed into a profound platonic one is a highlight of the book. Some of his nearly 50 movies are discussed in depth, others briefly remarked upon and others mentioned in passing. A flaw of the book is a seeming lack of editorial scrutiny. Some statements are repeated later on again, sidetracking the work’s smooth flow.

Shifting from levity to clinical straightforwardness, Allen offers his account of the 1992 scandal and its aftermath. Soon-Yi, Mia, Dylan and Ronan Farrow are depicted from his often harsh perspective as he proclaims his innocence of the accusations of sexual molestation.

Once a cultural icon, Woody Allen is at present a polarizing figure in the United States, and Apropos of Nothing will enforce his admirers’ adoration and his detractors’ scorn.

Harold Pinter’s 1989 television adaptation of Elizabeth Bowen’s novel, The Heat of the Day is faithful yet showcases his renowned style. This W.W. II tale of romantic and political intrigue in London during The Blitz is a perfect vehicle for Pinter’s pauses, coolness and subtext. Michael Gambon, Michael York and the always welcome Patricia Hodge portray the wily triangle under Christopher Morahan’s atmospheric direction. I came across it for the first time on YouTube for free.

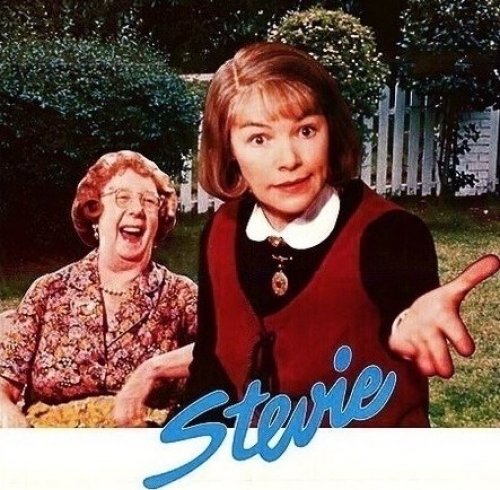

Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne indelibly recreated their 1977 London stage performances in director Robert Enders’ inspired cinematic treatment of author Hugh Whitemore’s screenplay of his stage play, Stevie. Mr. Whitmore cleverly employs flashbacks, in-person narration and direct address to the camera during his biographical fantasia.

Ms. Jackson is in all her glory portraying the eccentric unmarried depressed award-winning English poet Stevie Smith (1902-1971) and Ms. Washbourne plays her nurturing unmarried aunt with animated warmth. The film tenderly tracks their suburban lives and close bond over several decades. Zesty Alec McCowen is charming as Stevie’s ill-fated love interest and Trevor is at his most commanding as the narrator and as a friend of Stevie’s.

My fond memories of seeing it long ago were affirmed by chancing upon it on YouTube for free. It’s simple depiction of ordinary lives and small pleasures are quite comforting. “Oh, Peggy! Junket!” joyously roars the latterly ancient aunt when presented with a dish of a special dessert.

The history of this 1978 film is noteworthy. It had a British engagement and a token run in Los Angles, without getting released in the United States. Still Jackson and Washbourne were nominated for Golden Globes as Dramatic Best and Best Supporting Actress respectively. Washbourne won the Los Angeles Film Critics Circle Award for Best Supporting Actress and was nominated in the same category by the British Academy of Film and Television.

In July 1981, Manhattan’s prime revival theatre, the Thalia, held a festival of films unreleased in the United States. Stevie was scheduled for a two day stand which sold out following New York Times film critic Vincent Canby’s rave review, ”Stevie has only four characters in it, but it is a very big, beautiful film about a restlessly rambunctious soul. It deserves to stay around indefinitely.”

It did. It was picked up for distribution, becoming an art house hit and was showered with accolades at the end of the year. The National Board of Review and The New York Film Critics Circle each gave their leading and supporting actress awards to Jackson and Washbourne. However, because of the Los Angeles screening three years earlier, the was film ineligible for the Academy awards. Jackson and Washbourne’s are often cited as two of the greatest film performances not nominated for Oscars.