By: Darryl Reilly

If you think hearing the N-word shouted countless times by stereotypical Black characters is funny, you’ll be in hysterics during much of Ain’t No Mo’s one hour and 50 minutes. Playwright Jordan E. Cooper’s uneven series of connected-satirical sketches had an acclaimed 2019 run at the Public Theater. It would made have for a provocative Netflix special, instead it’s been moved to Broadway with dire commercial results.

Despite uniformly rave reviews from the major theater critics, it’s closing after a few weeks due to poor ticket sales. Celebrities such as Will and Jada Smith, Tyler Perry and Queen Latifah, have bought out and hosted performances, distributing free tickets to it. This Hail Mary pass did keep the play running a few more days, but indifference among Black and white full price-paying Broadway theatergoers was insurmountable.

The 27-year-old Mr. Cooper is being touted as Broadway’s youngest Black playwright, which is a landmark, but Ain’t No Mo’ is well-publicized juvenilia. Fitfully entertaining, it is decidedly not a major work of dramatic literature. The Obie-winning Cooper has had a meteoric rise in the television industry as a writer, performer and showrunner. Ain’t No Mo’ is reminiscent of counterculture stage works of the 1960’s, and edgy 1970’s films which expressed militant and valid views on race relations in the U.S.

Ain’t No Mo’s conceit is that in the near future, an authoritarian American government is funding the airfare for all Black citizens to resettle in Africa. It is made clear that those who remain in the country will face ominous consequences. Cooper offers a collection of uneven scenes depicting characters facing the decision to stay or go.

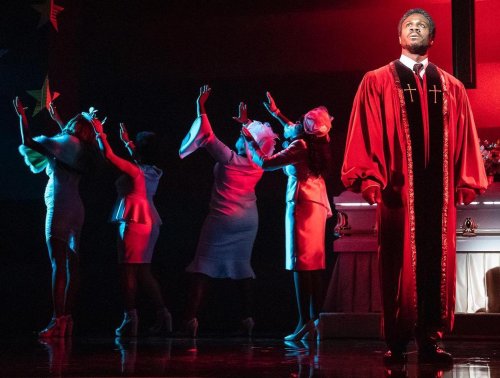

The opening is a trusty gospel church routine with a fiery pastor and zany parishioners. A Black Real Housewives-style sequence demonstrates that the show is all fake, with the producer cueing the bogus participants as to what to say and how to say it. In a lavish dining room, a wealthy Black family behaves just as snooty and imperiously as white upper-class grandees. Cooper’s writing is professional and technically adept, but none of these scenes really land as they’re tired and derivative, to those with a sense of history.

However, two sequences are well-written and are jolitngly executed. In an abortion clinic waiting room where millions of clients are seeking such services, a woman and her husband debate her having the procedure which she desires, and he’s against. The chilling revelation is that he is a figment of her imagination; he was shot to death by the police. A wrenching prison scene has two inmates being given the reward of early release in return for their going to Africa. The plight of the Black under-class and the odious power structure of incarceration is dramatized with painful depth.

The strong cast of Fedna Jacquet, Marchánt Davis, Shannon Matesky, Ebony Marshall-Oliver and Crystal Lucas-Perry, all enact their multiple often cartoon-like roles with gleeful histrionic force, which is pleasurable to experience.

Three of Ain’t No Mo’s interconnected scenes take place at the airport where the last flight to Africa is being boarded and will be piloted by Barack Obama. Peaches, the harried drag queen flight attendant, appears solo at the gate dispensing sassy observations. In the tradition of Noël Coward, who often wrote “a roaring part” for himself, Cooper plays Peaches. He has stage presence, is amusing and exhibits emotional range.

Director Stevie Walker-Webb fulfills Cooper’s vision through rapid pacing, visually compelling physical staging and the cast’s vivid performances. Scenic designer Scott Pask grand components represent the various locations with optic flair, particularly the church, prison and airport. Mr. Pask’s creations swiftly merge from one to the next, allowing for smooth scene transitions.

Emilio Sosa’s fabulous costume design outrageously, starkly and simply realizes each character with distinction. That sense of individuality is complemented by Mia M. Neal’s striking wig design. Lighting designer Adam Honoré and co-sound designers Jonathan Deans and Taylor Williams, augment the piece’s theatricality with their accomplished work.

Depending on one’s sensibility, one could either be laughing continuously, or be in stupefied silence during Ain’t No Mo’. The play does have merit for attempting to boldly tackle the corrisive subject of the Black American experience, but ultimately it is heavy-handed agitprop laced with strained humor. It’s concerns have been executed more effectively before.

Film critic Elvis Mitchel’s Netflix documentary, Is That Black Enough for You?!? is his hard-edged, though affectionate and definitive take on the 1970’s blaxploitation film genre. For a brief time, Black directors and screenwriters had opportunities to put the Black American life fiercely, realistically and profoundly on the screen.

For the stage, Amiri Baraka’s piercing NYC subway-set 1964 Dutchman was a groundbreaking and unsettling American racial allegory. In 2017, the Negro Ensemble Company commemorated its 50th anniversary by presenting a double-bill revival of two over-looked 1960’s biting one-act plays, “Rosalee Pritchett” and “The Perry’s Mission,” which are among the troupe’s most seminal works. They are mind blowing, arguably influenced and are far superior to Ain’t No Mo’. My review is linked below.

Ain’t No Mo’ (through December 23, 2022)

Belasco Theatre, 111 West 44th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit www.aintnomobway.com

Running time: one hour and 50 minutes with no intermission